PHEVs a ‘con’ says pro-EV European campaign group

“Plug-in hybrid con” is the attention-grabbing headline of a recent briefing paper from a major European clean transport campaign group. It claims real-world CO2 emissions of PHEVs are much, much higher than official test values. But the findings are as much a reflection of poor driver behaviour and even poorer government policy design as flawed engineering.

Transport & Environment, a 30-year-old independent non-profit activist organisation with Europe-wide support, combined reputable studies of real-world PHEV emissions from the Netherlands, Germany, France, Poland, Sweden and the UK. It found, on average, carbon dioxide emissions were more than two-and-a-half times greater than those obtained in official tests.

After analysing data from around 20,000 PHEVS in use by both fleets and private owners, T&E calculated their CO2 emissions were typically about 117g/km, instead of the 44g/km average indicated by their results in the standard New European Driving Cycle test. Australia’s official consumption and emissions test is basically the NEDC with some minor modifications.

This means PHEVs’ actual CO2 emissions are only slightly better than the real-world 135g/km of a normal hybrid like a Toyota Prius, according to T&E. In turn, this number is only a relatively small improvement over normal petrol- and diesel-powered vehicles, which in Europe have been found to have average real-world CO2emissions of around 165g/km.

“It is clear PHEV emissions are much more comparable to those of conventional cars than electric cars,” argues T&E.

The organisation provides estimations of lifetime CO2 emissions to support its point. Over a realistic 190,000km lifetime of use, conventional cars will emit more than 10 times as much of the gas as an EV powered by the (rapidly decarbonising) UK electricity grid. For a plain hybrid the factor is more than eight times, and for a PHEV it’s above seven.

What’s going on?

Firstly, those high real-world PHEV CO2 emissions means they’re not being driven in electric mode very often.

PHEV sales in Europe are booming. In the UK, for example, they’ve selling three times faster now than in 2019. The range of choice is growing fast; T&E estimates there will be 100 different models on sale there by the end of the year.

Two factors are at work. Manufacturers have an incentive to sell PHEVs. They’re a way to lower fleet-average CO2 emissions numbers, as required by European law. At the same time, businesses are encouraged to buy. Company car taxes on PHEVs in the UK are only 40 percent those for conventional cars. As a result, PHEVs are taking over from diesels as the default choice for company cars.

Once the PHEV has been sold there is no incentive for its driver to run it on electricity as much as possible. Why would someone provided with a company PHEV and fuel card ever bother to plug it into a socket to recharge with electricity they have to pay for themselves? Assuming, of course, they have a power outlet that’s practicable to use.

They don’t. Tales of big-mileage business drivers returning PHEVs with obviously unused charging cables are becoming common in the UK.

Car makers must also bear some of the responsibility. T&E reports that all of the 10 most popular PHEVs sometimes run their internal combustion engines even when the driver has selected electric-only mode. The list includes Europe’s biggest-selling PHEV, the Mitsubishi Outlander, as well as more costly examples such as the Range Rover, Range Rover Sport, Volvo XC90, Mercedes-Benz E-Class and Mini Countryman.

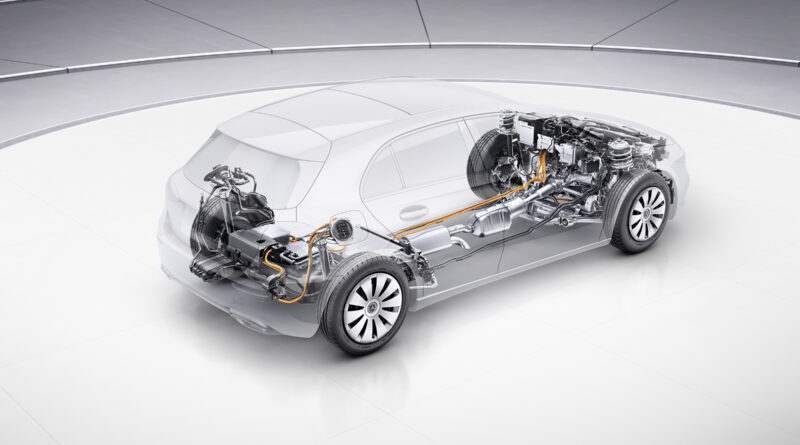

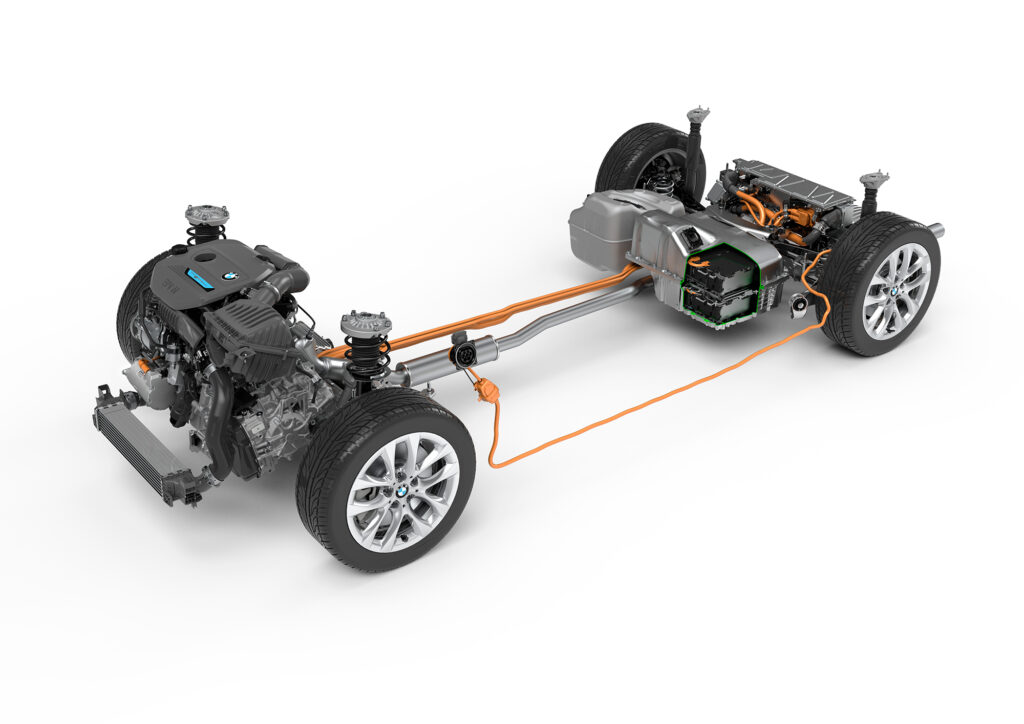

Low ambient temperatures are the most common trigger for start-up while in EV mode. This is because a PHEV uses the excess heat lost by its engine to the cooling system to provide cabin warmth. But high temperatures can have the same effect. In many PHEVs the air-conditioning system compressor is powered by the engine.

Other causes of engine start-up in EV mode include pressing the accelerator all the way to the floor, exceeding a pre-set EV mode speed or even, in at least one case, switching on adaptive cruise control.

“The reality is it is almost impossible for the car (PHEV) to drive in zero-emission mode even for short distances on a regular basis,” according to T&E.

The organisation is calling for an end to the tax breaks contributing to the surging popularity of PHEVs in Europe. T&E argues that they are “entirely unjustified based on the way PHEVs are typically used by their owners”.

Such a move, the organisation says, would be good for EVs. “By raising the tax it would also encourage higher sales of battery electric cars”.