Kia Niro review: does a Hybrid or Plug-in make sense?

“Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) are costly and compromised things that often fail to deliver much in the way of environmental benefit.”

A quote from my esteemed colleague John Carey from his opinion piece titled “Why plug-ins don’t make sense.”

Needless to say it got people talking, as any good journalism should.

Carey’s two-week, 900km experience with a Mini Countryman PHEV was core to his anti-plug-ins argument. It’s certainly worth a read to enjoy the bile thrown at PHEVs while he points you in the direction of full EVs or ‘normal’ hybrids.

Many commented on our website and social media.

“A PHEV is having the best of both worlds: drive electric for local trips and ICE (petrol) when you must when going cross country,” said Ferdinand Gutig.

Volvo XC40 Recharge owner Mike Paine opined: “I certainly don’t regard my PHEV as a poor compromise. The EV range is about 35km which means nearly all my urban trips are pure electric. We did a 3500km trip to Carnavon Gorge in Queensland which would have been near-impossible with a BEV.”

Peter Douglas meanwhile sided with our man Carey. “I have always thought that plug-ins seemed to be a half-baked way to achieve efficiency; my thinking is to dive in and go full electric or nothing.”

It’s not that simple…

Here’s my ten cents. Everybody’s circumstances are different and they dictate whether an EV, PHEV or hybrid works best.

I’ve got two primary school-age kids, live in coastal town suburbia and make the occasional 250km round trip into Brisbane.

Epic road trips? Sorry. Not for us. The kids don’t want to be shackled for that long – interstate trips (when they’re allowed) are done by ‘plane. This, I know, is the reality for many Aussie families these days.

On paper, I can make a decent argument for us having a PHEV. We do lots of short urban trips – school run, supermarket, sports grounds, visiting grandparents – where we can use only electric power.

When Brisbane trips roll around, no need to worry about charging infrastructure or stopping to recharge. The petrol engine can do its thing after the electric batteries are exhausted.

Carey wrote: “Having to plug in every single day can become tiresome. I know this from experience with a variety of test cars.”

Here’s where I disagree. It’s not tiresome at all. I have a garage (homes outside city CBDs typically do) and can park a PHEV or EV right beside my power point. I drive in, open my car door, pick up the charge cable and slot it in the socket. Ten second job. On good days one of my kids will greet me and do the plugging in for me.

I can’t disagree with Mr Carey about some of a PHEV’s negatives. The battery adds extra weight and cost over a normal hybrid, while having a petrol engine means you still endure the service costs associated with them (oil changes, timing belts, etc.), all avoided with a full EV.

Ideal. But what if you can’t afford a full EV? A Kia Niro Electric S starts from $62,590 before on-roads. The Plug-in version is $46,590. A Hybrid? $39,990. The $6600 jump from Hybrid to PHEV is far more palatable than the PHEV to EV’s $16,000.

I already know I can make a full EV work as the family’s daily driver with little effort. We’d own one if there was one that suited our needs and was within our budget. So using the Kia Niro as a test, would we be better off paying the $6600 more for the PHEV version, or do as Carey preaches and just go Hybrid?

Week One – Kia Niro PHEV

About the same size as a Kia Seltos – but with a longer wheelbase for better rear space – the Niro small SUV is a decent shout to suit a young family of four.

We’ll ignore the fact it’s an old model even if it’s only been recently introduced to Australia, and my full review of it can be found here.

On collection, range anxiety’s clearly not going to be a thing. The smart digital readout shows 50km electric range and 800km petrol range. A combined 850km. Reassuring.

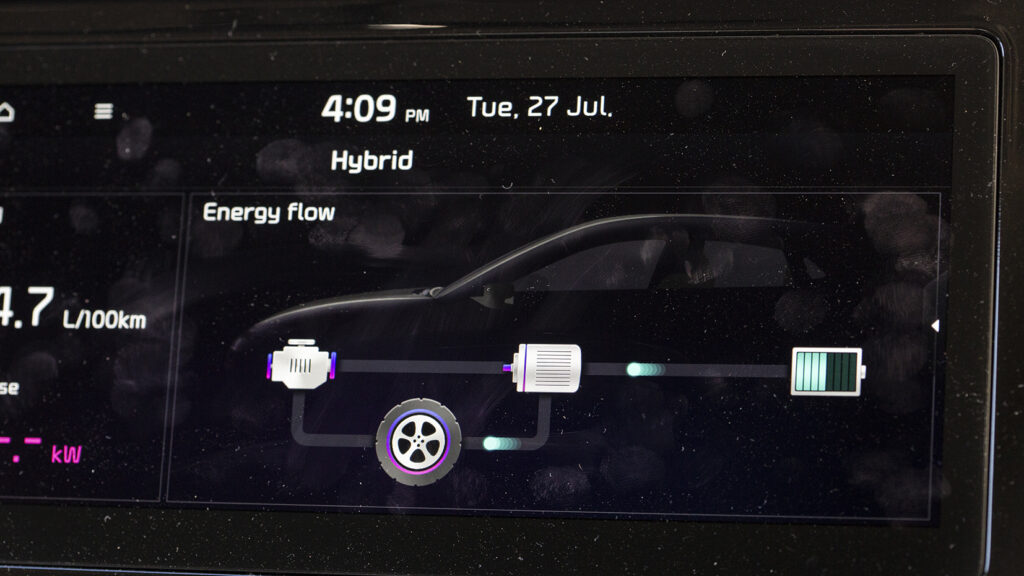

Straight onto the motorway home and the electric motor and petrol work in unison. I leave it in Auto Mode where the car decides how to share propulsion duties, and see it’s quickly chewing through my battery charge.

Ideally, I’d want the car to realise we’re travelling at 110km/h and run purely on petrol. I do the job for it. A button moves it into ‘Hybrid’ mode and it stops drawing power from the battery. Best to save this in case I encounter traffic or when I’m stop-start town driving – this is when you want to run on electric.

My 142km journey – the vast bulk of it motorway – returns 3.4L/100km. Not bad as the electric motor was off for most of the trip.

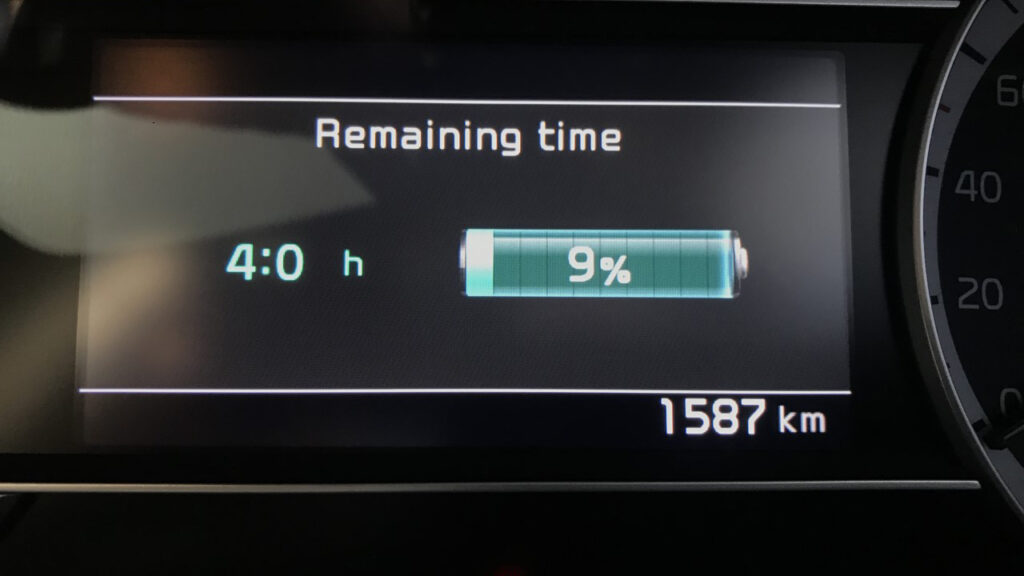

Into the garage and plug it in. With 9% battery charge remaining I’m told it’ll take four hours to refill. This is just using the normal domestic 10amp socket. All good there, it’ll be full by the time it comes to collect the kids from school.

Fully charged, I select EV mode – which should keep the petrol engine dozing – for the 10km return trip to pick up the kids. It’s blissfully quiet like this. The Niro PHEV is well insulated and hums along as silently as the full electric version.

That changes when I pull out of my road. Going for a gap in the traffic I need a heavy-ish throttle. The car detects I want more performance than the electric motor alone can offer (it’s only 44.5kW and 170Nm) and I feel the guilt as fossil fuels begin to burn as the 1.6-litre petrol engine joins the party. Oops.

I learn to keep throttle presses light, and I manage the rest of the trip in EV mode.

Steering wheel paddles offer three different levels of regeneration (plus completely off). The Niro slows as it harvests energy, but doesn’t come to a complete stop like, say, a Hyundai Kona Electric or Nissan Leaf. I’d prefer it if it did – it saves brake pads and not using a brake pedal in town is a rewarding part of electric car driving.

Over the next few days I monitor the trips we make. Typically all are between five and 25 kilometres. Our fuel economy return for these trips – viewed through the Kia’s monitor – are 1.0L/100km, 0.3L/100km, 2.5L/100km, 0L/100km, 0.8L/100km and 3.9L/100km. I forgot to put it in EV mode on the last one.

After 706km in total, the final economy figure is 3.1L/100km. About 300km of that, inevitably, was on the motorway collecting and returning the car. But importantly, when used in town – and you must select EV Mode – petrol use was zero or minimal.

Only AC outlets can charge the Niro PHEV. I’ll admit to a schoolboy error. I pulled into a charging station to use a fast AC charger and remembered I’d left the Niro’s charge cable plugged in to my garage wall. Not a good look.

READ MORE: What’s the difference between AC and DC electric car charging?

On the practicality front, the PHEV is the Niro with the smallest boot – a not great 324L. Underneath is no space saver spare, just a repair kit and the battery.

We also had problems with the PHEV’s heater during the depths of a cold snap. Running in electric mode it just fired out cold air, no matter how high the temperature was turned up. Once the petrol engine was on it did cough out the required heat, but this failed to help our eco credentials.

Unlike a Nissan Leaf, there’s no button for ‘Heat’ to turn the heater on. Kia couldn’t explain the problem and suggested it could be an issue with that certain car. However, the same quirk was reported by EVcentral’s Toby Hagon during his test of the Niro PHEV.

Week Two – Kia Niro Hybrid

At $6600 less outlay, the Niro Hybrid’s a decent chunk cheaper than the PHEV.

That said, its $39,990 asking price puts it on par with a Toyota RAV4 GXL Hybrid 2WD. The Niro Hybrid offers 3.7L/100km versus the RAV4’s 4.7L/100km, but the Toyota is bigger and, as the market has shown, markedly more desirable.

But let’s focus on how it did against the Niro PHEV.

We used it in the same way as the plug-in version: 300km of motorway use then about 400km of daily duties: short journeys and a bit of traffic included.

Frustratingly, while sitting in traffic you can’t select an EV-only mode. You can do in Toyota’s Hybrids (like the RAV4), and I like this for sitting in stop-start traffic up to about 20km/h. The Niro Hybrid is beautifully smooth when it rolls just on electric, but seems too keen to turn on the petrol at low speed.

Just like the Niro PHEV, the Hybrid’s output is 104kW/265Nm – 77kW/147Nm from the four-cylinder petrol, plus 32kW/170Nm from the electric motor.

With a dual-clutch auto gearbox it helps free up what power the motors provide in an eager manner – certainly more so than a CVT gearbox as found in Toyota hybrids.

But the Niro Hybrid can feel jittery at low speeds, and when the petrol engine pipes in it’s not the smoothest of transitions. If you ask for regen through the steering wheel paddles (as in the PHEV) progress feels even more stuttering.

More positively, the Hybrid’s boot is a family-friendlier 410L, plus there’s a space saver spare wheel under the floor. Oh, and the heater works properly.

Tale of the tape was a return of 4.8L/100km over our 700km test. That meant our everyday use was about 1.7L/100km more in the Hybrid than the PHEV.

If we travelled 15,000km per year, that would mean we’d use about an extra 255-litres of petrol in a Niro Hybrid over a Niro PHEV. At $1.50 per litre, that’s under $400.

Conclusion? Maybe wise old sage Carey was right. “The only circumstance when a PHEV is doing something good for the planet is when it’s driving purely on electric power,” he said.

If we could eliminate those journeys over 50km the PHEV makes a stronger point for itself. It’s possible if the boundaries of your travels really are that short. Or – and I suspect this may be most relevant – the PHEV is a second car in the family and is used selectively for these short trips.

Even so, it’s going to take a long time to recoup that $6600 higher sticker price.

Thank you for a really fair, objective assessment of what is, for many people, not a clear-cut choice. In many cases, the best choice right now is probably to delay any purchase for a year or two, if you possibly can. The problem is that cars can be expected to last for twelve or fifteen years, maybe more, and what is the best choice today will not be the best choice in even five years, never mind ten or twelve years. Hybrids and plug-in hybrids are going to be emitting just as much carbon dioxide in five or ten years time, and there are going to be better EV choices at a reasonable price. However, one could argue that right now a PHEV or even a mild hybrid looks like quite a good use of resources, especially while battery supply is struggling to meet demand. What is missing from the discussion is the fact that hybrids and PHEVs are very poor examples of electric vehicles. The P in PHEV could well stand for “puny”, because that is what you get – a very modest electric motor with a considerably more powerful IC engine. So you miss out on most of the pleasure of driving an EV – the silent exhilarating acceleration from a standstill right through the speed range, and the instant response.